While the U.S. Talks of War, South Korea Shudders

There is no war scenario that ends in victory.

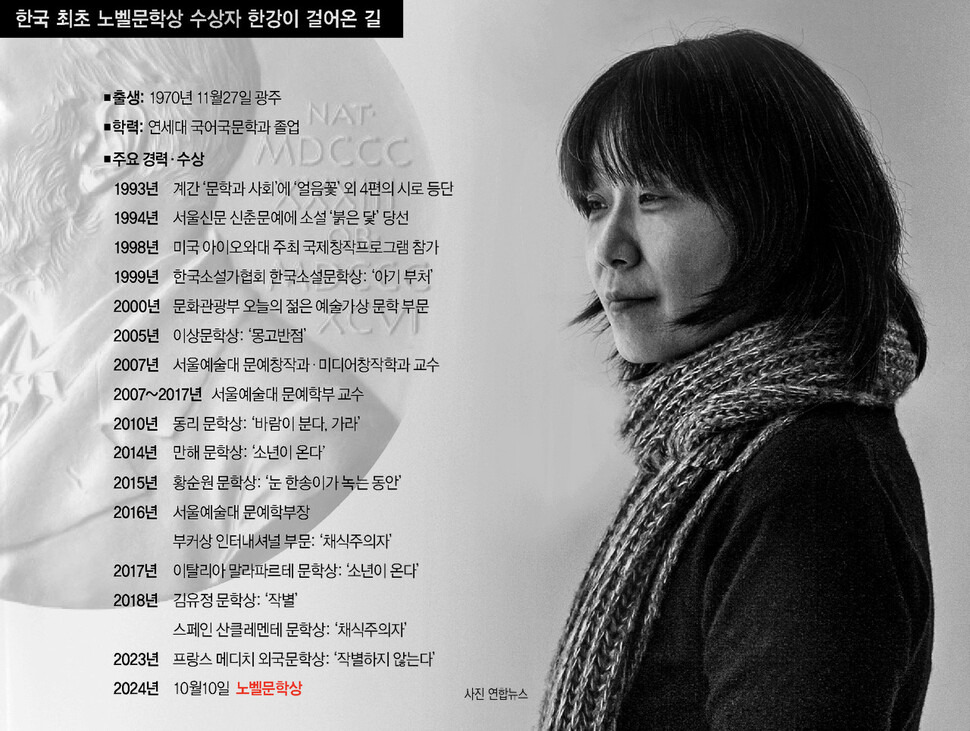

By HAN KANGOCT. 7, 2017

I cannot turn my thoughts from the news article I happened to see a few days ago. A man in his 70s accidentally dropped two thick wads of cash in the street. Two people who happened upon this bundle of money and shared it between them were caught by the police, made to give up the money and charged with theft.

Up until here, it is still an ordinary story. But there was a special reason this man was carrying so much cash on him. “I’m worried that a war might be coming,” he told the police, “so I’d just taken my savings out of the bank and was on my way home.” He said that it was money he had saved — a little bit each month — for four years, intended to send his grandchildren to college. Since the Korean War broke out in 1950, war would have been the enduring experience of this man’s adolescence. I imagine what he would have been feeling, a man who has lived an ordinary middle-class life ever since, on his way to the bank to take out his savings. The terror, the unease, the impotence, the nervousness.

Unlike that man, I belong to the generation that never experienced the Korean War. Crossing the border to the North was already impossible before I was born, and even now it is forbidden for Southerners to meet or have contact with Northerners. For those of us of the postwar generation, the country known as North Korea is at times felt as a kind of surreal entity. Of course, rationally, I and other Southerners are aware that Pyongyang is only two hours by car from Seoul and that the war is not over but still only at a cease-fire. I know it exists in reality, not as a delusion or mirage, though the only way to check up on this is through maps and the news.

But as a fellow writer who is of a similar age to me once said, the DMZ at times feels like the ocean. As though we live not on a peninsula but on an island. And as this peculiar situation has continued for 60 years, South Koreans have reluctantly become accustomed to a taut and contradictory sensation of indifference and tension.

Now and then, foreigners report that South Koreans have a mysterious attitude toward North Korea. Even as the rest of the world watches the North in fear, South Koreans appear unusually calm. Even as the North tests nuclear weapons, even amid reports of a possible pre-emptive strike on North Korea by the United States, the schools, hospitals, bookshops, florists, theaters and cafes in the South all open their doors at the usual time. Small children climb into yellow school buses and wave at their parents through the windows; older students step into the buses in their uniforms, their hair still wet from washing; and lovers head to cafes carrying flowers and cake.

And yet, does this calm prove that South Koreans really are as indifferent as we might seem? Has everyone really managed to transcend the fear of war? No, it is not so. Rather, the tension and terror that have accumulated for decades have burrowed deep inside us and show themselves in brief flashes even in humdrum conversation. Especially over the past few months, we have witnessed this tension gradually increasing, on the news day after day, and inside our own nervousness. People began to find out where the nearest air-raid shelter from their home and office is. Ahead of Chuseok, our harvest festival, some people even prepared gifts for their family — not the usual box of fruit, but “survival backpacks,” filled with a flashlight, a radio, medicine, biscuits. In train stations and airports, each time there is a news broadcast related to war, people gather in front of the television, watching the screen with tense faces. That’s how things are with us. We are worried. We are afraid of the direct possibility of North Korea, just over the border, testing a nuclear weapon again and of a radiation leak. We are afraid of a gradually escalating war of words becoming war in reality. Because there are days we still want to see arrive. Because there are loved ones beside us. Because there are 50 million people living in the south part of this peninsula, and the fact that there are 700,000 kindergartners among them is not a mere number to us.

One reason, even in these extreme circumstances, South Koreans are struggling to maintain a careful calm and equilibrium is that we feel more concretely than the rest of the world the existence of North Korea, too. Because we naturally distinguish between dictatorships and those who suffer under them, we try to respond to circumstances holistically, going beyond the dichotomy of good and evil. For whose sake is war waged? This type of longstanding question is staring us straight in the face right now, as a vividly felt actuality.

In researching my novel “Human Acts,” which deals with the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, when the military dictatorship turned to the armed forces to suppress student protests against martial law, I had to widen the field to include documents related not only to Gwangju but also to World War II, the Spanish Civil War, Bosnia and the massacres of Native Americans. Because what I ultimately wanted to focus on was not one particular time and place but the face of universal humanity that is revealed in the history of this world. I wanted to ask what it is that makes human beings harm others so brutally, and how we ought to understand those who never lose hold of their humanity in the face of violence. I wanted to grope toward a bridge spanning the yawning chasm between savagery and dignity. One of the many things I realized during my research is that in all wars and massacres there is a critical point at which human beings perceive certain other human beings as “subhuman” — because they have a different nationality, ethnicity, religion, ideology. This realization, too, came at the same time: The last line of defense by which human beings can remain human is the complete and true perception of another’s suffering, which wins out over all of these biases. And the fact that actual, practical volition and action, which goes beyond simple compassion for the suffering of others, is demanded of us at every moment.

The Korean War was a proxy war enacted on the Korean Peninsula by neighboring great powers. Millions of people were butchered over those three brutal years, and the former national territory was utterly destroyed. Only relatively recently has it come to light that in this tragic process were several instances of the American Army, officially our allies, massacring South Korean citizens. In the most well-known of these, the No Gun Ri Massacre, American soldiers drove hundreds of citizens, mainly women and children, under a stone bridge, then shot at them from both sides for several days, killing most of them. Why did it have to be like this? If they did not perceive the South Korean refugees as “subhuman,” if they had perceived the suffering of others completely and truly, as dignified human beings, would such a thing have been possible?

Now, nearly 70 years on, I am listening as hard as I can each day to what is being said on the news from America, and it sounds perilously familiar. “We have several scenarios.” “We will win.” “If war breaks out on the Korean Peninsula, 20,000 South Koreans will be killed every day.” “Don’t worry, war won’t happen in America. Only on the Korean Peninsula.”

To the South Korean government, which speaks only of a solution of dialogue and peace in this situation of sharp confrontation, the president of the United States has said, “They only understand one thing.” It’s an accurate comment. Koreans really do understand only one thing. We understand that any solution that is not peace is meaningless and that “victory” is just an empty slogan, absurd and impossible. People who absolutely do not want another proxy war are living, here and now, on the Korean Peninsula.

When I think about the months to come, I remember the candlelight of last winter. Every Saturday, in cities across South Korea, hundreds of thousands of citizens gathered and sang together in protest against the corrupt government, holding candles in paper cups, shouting that the president should step down. I, too, was in the streets, holding up a flame of my own. At the time, we called it the “candlelight rally” or “candlelight demonstration”; we now call it our “candlelight revolution.”

We only wanted to change society through the quiet and peaceful tool of candlelight, and those who eventually made that into a reality — no, the tens of millions of human beings who have dignity, simply through having been born into this world as lives, weak and unsullied — carry on opening the doors of cafes and teahouses and hospitals and schools every day, going forward together one step at a time for the sake of a future that surges up afresh every moment. Who will speak, to them, of any scenario other than peace?

Opinion | While the U.S. Talks of War, South Korea Shudders (Published 2017)

There is no war scenario that ends in victory.

www.nytimes.com

'세상에 말걸기' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 이제야 꽃을 드노니 (0) | 2022.11.14 |

|---|---|

| 백장암 도로명주소 변경 (0) | 2019.05.16 |

| 질문의 방식 (0) | 2018.11.23 |

| 미얀마 여행 (0) | 2016.12.07 |

| 삶으로부터의 혁명을 읽고 (0) | 2016.11.05 |